Climate change affects every part of our planet and Iceland is no exception. Extensive scientific study has mapped likely impacts on the country and as more research is published, our understanding of the consequences increases. In this article we’ll take a look at glacier retreat and climate change to explore what’s happening in Iceland.

Temperature increase is a sustained trend

Iceland has a maritime climate, and its mid-Atlantic location means that it is considerably warmer than you might expect of a country at this northerly latitude. However, the past was quite a contrast to the situation we find ourselves in at present. During the Little Ice Age, Icelandic weather was noticeably different to that which we experience today – in the late 19th century, the coldest period, we know that sea ice reached the Icelandic coast.

Temperatures have been on a warming trend for more than a hundred years. It’s an accelerating rate: the increase in temperature has been most pronounced in the last thirty years. The Icelandic Met Office reported that there’s been a rise of approximately 0.47°C per decade. This might not seem a lot, but it’s significant – and about three times faster than the global average. New report has however shown that the year 2024 was the coldest in Iceland this century. Elsewhere in the world the temperatures records are being broken every year.

Within Iceland, the impact varies, with the north and west experiencing greater change than the area covered by Vatnajökull. Precipitation, too, is increasing. Rainfall totals are showing an upward trend both in the lowland regions where much of the Icelandic population lives and also in the sparsely populated central highlands. More intense storms are also likely in the future. blue ice caves as well as it helps keep us safe.

Where to find ice in Iceland

One of the most obvious effects of climate change in Iceland is of course glacier retreat. Ice currently covers around 11% of the country’s area. Vatnajökull is the largest by a huge margin. If you include its many outlet glaciers then this ice covers about 8% of Iceland; its volume is about 3000 km3 in total. One of these outlet glaciers is Fjallsjökull, the glacier which feeds Fjallsárlón Glacier Lagoon.

Though Iceland’s other glaciers are smaller, they aren’t insignificant. Langjökull, Hofsjökull, Mýrdalsjökull and Drangajökull are all sizeable bodies of ice. There are also many more smaller glaciers scattered across the country. The Tröllaskagi peninsula contains the most, and you’ll find as many as 150 separate cirque and valley glaciers in that part of North Iceland, though of course they’re a fraction of the size of mighty Vatnajökull.

Receding glaciers

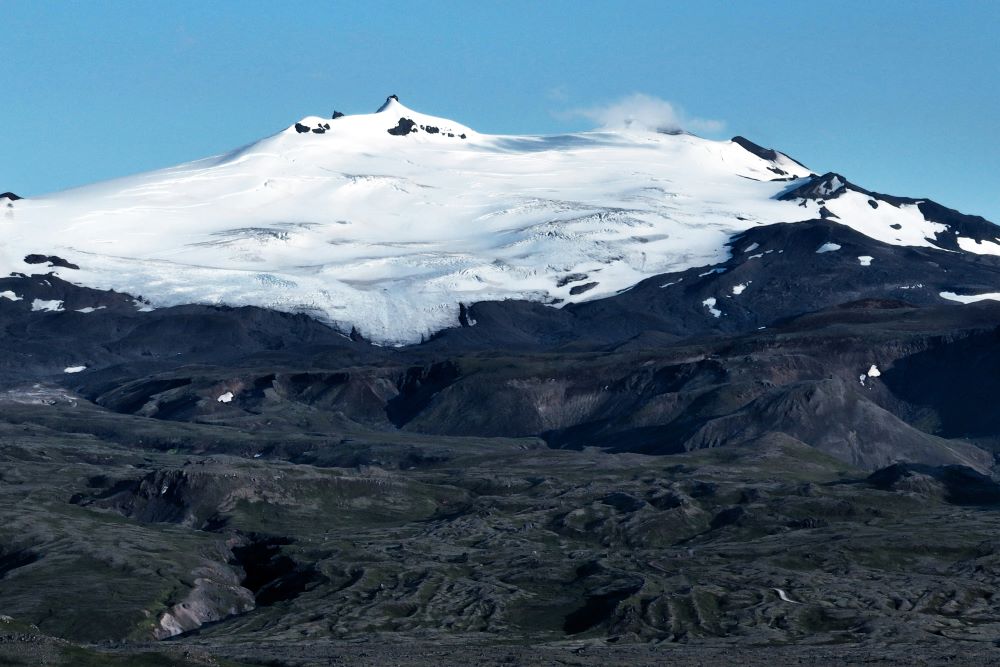

Most of the world’s glaciers are receding and Iceland is experiencing this as well. Predictions are alarming and in a worst case scenario, some climatologists have suggested that Icelandic glaciers could vanish within 100 years, and almost certainly within the next 200. Glacial retreat is already evident in many areas, such as at Sólheimajökull and Snæfellsjökull, but according to most models, the rest may follow within a couple of centuries.

Getting the message across has been difficult, particularly as the vast size of Vatnajokull makes it hard to imagine Iceland devoid of ice. Yet the first Icelandic glacier to officially lose its status, Okjökull, was formally declared gone a decade ago. Famously, a ceremony was held at the site five years later to mourn its loss and remind people that many other glaciers could follow. And large though Vatnajökull most certainly is, we cannot take even this enormous body of ice for granted.

The impact of climate change extends beyond the loss of the glaciers themselves

Though glacier retreat is a headliner when it comes to climate change, there are many other impacts that are equally worrying.

- Meltwater changes

As the volume of meltwater alters, glacial rivers find a different course and where water collects in hollows, lakes form. For example, the Icelandic Met Office noted that in 2009 the river Skeiðará migrated and its discharge now feeds the river Gígjukvísl, leaving for a time a redundant bridge over a dried up river bed.

The flood risk from glacial meltwater will be different in the future. Meteorologists predict that later this century the volume of meltwater will peak, increasing glacial river runoff. But over time, because of lower snowfall totals and thus little winter accumulation, the prevalence and scale of spring floods will consequently decrease.

Meltwater from these glaciers supplies Iceland’s major rivers and in some cases helps to generate hydro-electric power. Meltwater increases will, at least at first, facilitate an increase of perhaps 20% in hydro-electric power as early as 2050. However it should be noted that in order to harness such potential, investment will be needed in power plants and other infrastructure to take advantage of all this additional capacity.

-

- Uplift of land

One thing that large glaciers do is to exert a lot of pressure on the land that they cover. So it stands to reason that if the ice melts, the weight that it can put on what’s beneath it will be considerably less. Crustal uplift has already been observed in Iceland’s interior and the south east region.

For instance, according to the Icelandic Met Office, the land on which the town of Höfn sits is rising by about 10mm per year. Closer to the Vatnajökull ice cap, the figure is twice that. The changes are not seen across the country as a whole; Reykjavik, for example, is experiencing an uplift of only about 2mm per year.

- Impact on the oceans

Sea level changes – impacted by what happens to the Greenland ice sheet – are likely to affect Iceland. A difference in ocean temperature will impact on fish stocks. Species such as capelin and mackerel are already affected; the population of the former has declined while that of the latter has increased. Fish such as haddock and monkfish, once mainly found off the south coast of Iceland, are now also seen in the north. These changes have a marked effect on seabird colonies as well as seals and whales.

- Cultivation

It’s not all negative: plant production in Iceland will be easier if temperature averages rise. The vegetation mix seen in the country is likely to change, with more shrubs and a greater variety of tree species coupled with a potential reduction in mosses and lichens. The area given over to birch forest is up 9% since 1989. Continued change is likely to attract bird species that haven’t previously been seen in Iceland.

It’s also possible that there could be a long-term evolution of agriculture as the warmer climate could support crops that haven’t previously flourished. In the meantime, the use of geothermal energy to heat greenhouses used for growing plants such as tomatoes has proved successful. It’s also demonstrated that there could be sufficient demand for changes to agricultural production.

- Glacial lagoons

As meltwater increases and glaciers retreat, lagoons form – just like Fjallsárlón Glacier Lagoon and Jökulsárlón Glacier lagoon. In the future, it’s possible we’ll see an increase in the number of glacial lakes and potentially larger lagoons than exist at present as water that’s currently stored as ice is released to fill hollows and naturally occurring basins.

Iceland will need to adapt in terms of the way people interact with the landscape, whether that means changing practices or altering risk management strategies. Though awareness of the impact of climate change has increased, it may already be too late to prevent dramatic change. Of course, that brings challenges but also opportunities.

At a certain point, glacial retreat becomes irreversible, as we have already seen with Ok disappearance. However, Vatnajökull is still a vast body of ice and will be around for some time yet. Experience this breathtaking glacial environment on a visit to Fjallsárlón in Iceland: take a BOAT TRIP out onto the glacier-strewn lagoon, embark on a GUIDED HIKE over the glacier’s surface or set foot in a MAGICAL ICE CAVE hidden within it.