Glacier retreat is impacting every glacier in Iceland; some are affected to a greater extent than others. This means that the amount of ice is decreasing; in the process, this alters landscapes both in the immediate vicinity and further afield. In this article we’ll take a look at why this is happening and what changes are likely to occur in the future to places such as Fjallsárlón.

Glaciers are not stationary as they crawl slowly down the side of the mountains.

How do glaciers move?

Glaciers might look stationary when we admire them but in fact they are moving, just imperceptibly slowly. Though the ice is solid, it’s perched on a slope, so under the influence of gravity it moves downhill. As it does so, the friction that’s created between the underside of the glacier and the valley floor melts the bottom of the ice.

This meltwater then lubricates the underside of the glacier which in turn helps it to move more freely over the rocks beneath. In addition, the body of ice has a kind of plastic quality about it, which enables it to flex and bend slightly as it travels over rocks and bumps in the valley floor.

Glaciers form where snow accumulates in the mountains. It then crawls down the mountain and

Zones of accumulation and ablation

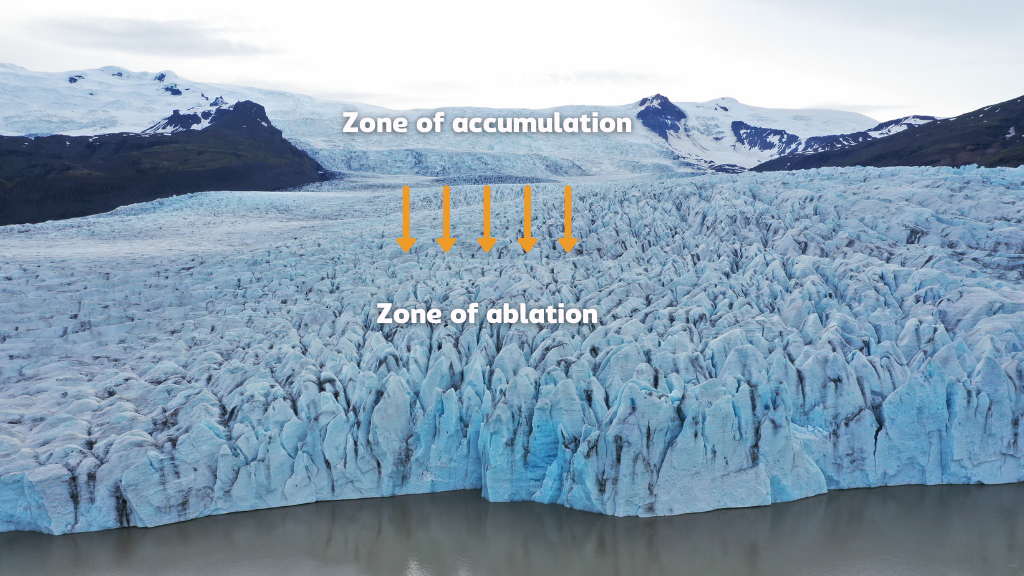

As the glacier is located on a mountainside, some sections of the ice are at a higher elevation than others. This is really important as the temperatures vary according to how high up you are. At the top of the glacier, which we call the zone of accumulation, it can be significantly colder. Snowfalls are compacted and turn first to firn and then to ice.

Lower down, the temperatures are higher. This means that where parts of the glacier are located in places that are above freezing, melting occurs on the surface of the ice. The end of the glacier, known as its snout, is in the warmest zone of all, which is where most melting happens.

As the glacier moves slowly down it collect a lot of material that It deposits in the ablation zone. Here we see Svínafellsjökull glacier.

Glaciers transport and deposit material

During the time that the glacier has been moving downhill, it has frozen around rock on the valley floor and sides, ripping them away in a process known as plucking. These pieces of rock are then transported along with the ice. But they weigh different amounts according to their size and when the ice melts, the glacial meltwater carries them varying distances before dropping them.

This process of deposition is why we have moraines; the rocks that are left ar the end of the glacier are called terminal moraine; where the glacier advances back over them – for instance when the temperatures fall the following winter – we rename them recessional moraines.

As the glaciers retreat, they leave behind a scarred surface like the outlet glaciers of Vatnajökull glacier.

Glacier retreat

As the bottom of the glacier melts, the ice vanishes and so the glacier effectively becomes shorter. We name this process glacier retreat as it appears that the glacier moves uphill. Water takes the place of what was once the solid ice and has to go somewhere. This is where those moraines come in: they form a barricade across the valley floor, blocking it off and trapping the water to form a glacial lagoon like Fjallsárlón.

Climate change means that the glaciers in Iceland – including Fjallsjökull, the glacier above Fjallsárlón – are shrinking. The rate of melting exceeds the new accumulations of snow and ice in the winter so overall, the amount of ice is getting less and less. Over time, the glacial lagoons are therefore growing – not only bigger but also deeper.

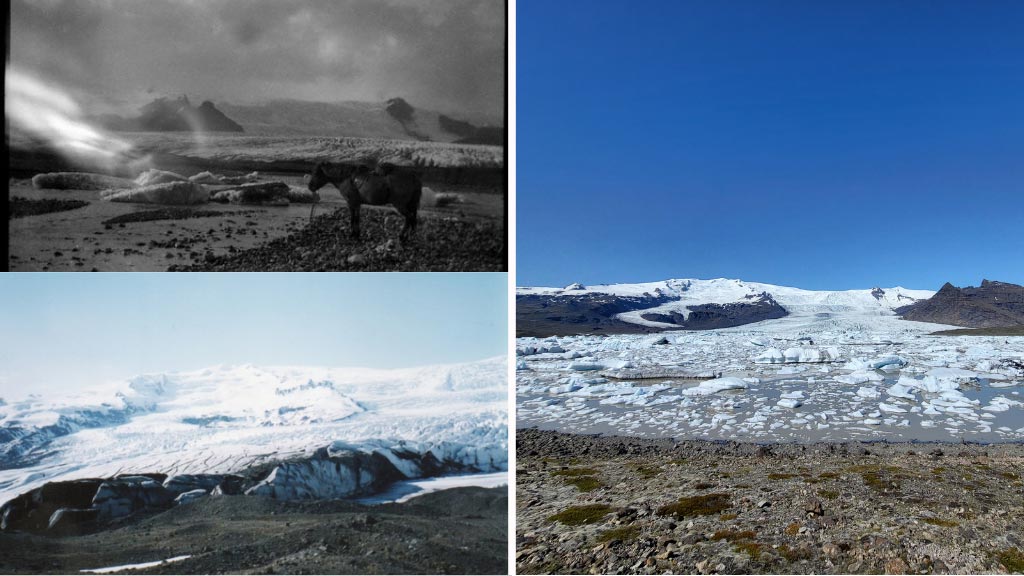

Here we can see the changes that Fjallsjökull glacier has gone through in the last century or so.

Changes in shape and size

Let’s drill down into the numbers. We know that Fjallsjökull is considerably smaller than it was in the 19th century. As the volume of ice shrunk, what was once a single tongue of ice split into two parts. In the period of 120 years leading up to 2010, almost a quarter of the ice and about a third of its volume was lost.

Initially, as early as 1936, small proglacial lakes began to form in front of Fjallsjökull glacier. By 1945, pictures exist of the lagoon we call Fjallsárlón. Scientists have carried out surveys at Fjallsárlón and their findings show that the glacial lagoon has grown considerably between 1945 and the present day.

According to an academic report published in 2024, the lake measured 45 metres deep in 1951 but this had increased to 119 metres by 2016. The predictions outlined in that study suggest that the lake will be at its largest by 2110 when it will be twice as large and contain three times as much water.

They expect that the lake will fill two deepened basins and at its deepest, the water will go down 210 metres. However, this is probably a good time to point out that glacial lagoons such as Fjallsárlón give us some of the most breathtaking views in Iceland, so although shrinking glaciers are a major concern, this is the silver lining – a lake that wouldn’t exist without the ice melting.

The melting of glaciers has a great impact on the environment around the glaciers.

How does this impact risk assessments and hazard monitoring?

These changes will also have an impact on mountain slopes higher up. Landslides, avalanches and rock falls are expected to occur, which could mean that rock tumbles from the valley walls into the water creating a wave. Monitoring happens constantly, so if you were planning on booking a boat trip out on the lagoon, rest assured that we always keep a close eye on any changes in the glacier and its surroundings.

Iceland’s many glaciers mean it is also prone to glacial lake outburst floods known as jökulhlaup. These floods send large quantities of water and whatever it’s carrying – chunks of ice, rocks and so on – down towards the coastal lowlands. To date, most of these have been triggered by sub-glacial volcanic activity and they are part and parcel of everyday life in Iceland to co-exist with the landscape and hazard monitoring is well-established, commonplace and accurate.

Iceland’s landscape is constantly evolving from melting glacier to erupting volcanoes.

The physical landscape of Iceland will continue to evolve

Change is normal in the fields of geomorphology and geology. The Icelandic landscape is constantly in flux and will continue to evolve as these processes continue. It’s important to understand people’s role in increasing the rate of global warming so that we can take steps to minimise our future negative impacts on the climate.

Whilst we wouldn’t want to underplay the seriousness of the situation facing Iceland and the rest of the world, we also acknowledge that we can’t change what’s happened in the past. Climate change has already created opportunities such as the chance to explore glacial lagoons like Fjallsárlón.

A floating iceberg on Fjallsárlón glacier lagoon that has recently broken of from the retreating Fjallsjökull glacier.

Fight for what matters

Without melting ice there’d be no lake, and no boat trips to absorb the jaw-dropping views of the glacier and the icebergs that have calved from it. For now at least, we still have an opportunity to get up onto the glacier and hike across its surface or step inside glittering subglacial ice caves.

As we do so, understanding how vulnerable these environments are will matter more to those who witness them first-hand as they’ll have made a direct connection. As a visitor to Fjallsárlón, you’ll see just how crucial it is to slow down the rate of glacial retreat going forward; your actions matter and any changes you make to reduce your carbon footprint will be important.