Glaciers and glacial lagoons are fascinating places. These mighty tongues of ice carve their way through the landscape like giant bulldozers. Though the rate of movement is too slow to observe with the naked eye, the evidence that it’s happening is all around us as the valley is shaped by the erosional power of the ice as it slides imperceptibly downhill due to gravity.

Visitors to Fjallsárlón can’t fail to be impressed by the landforms that they see around them – imagine how lucky we feel to spend so much time in a place as spectacular as this. In this article, we’ll take a brief look at the area’s geology and how the landscape has been eroded and shaped by the ice. Nothing beats seeing it with your own eyes, of course, so pay us a visit when you’re next in the area and let us show you our workplace on a boat trip or glacier hike.

What kind of landscape are we talking about?

Fjallsjökull is the ice that you see on the mountainside rising behind the lake. Fjallsárlón itself is that glacier lagoon. To explain this remarkable landscape, let’s start with the glacier, Fjallsjökull. This vast tongue of ice measures about 2 kilometres wide and around 1800 metres from the top of the mountain to the valley below. Even though it has entered a phase of retreat, it’s an impressive sight in its present state.

Behind the lagoon, you’ll see a mountain peak; it has a triangular shape. This is called Miðaftanstindur and it’s one of the landforms that make Fjallsárlón so utterly photogenic, as it provides a distinctive backdrop. Another thing you’ll quickly notice when you arrive is that the glacier and mountain peak feel very close; the lake is smaller than Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon and feels a lot more intimate.

High on the mountain, winter snowfalls collect in what geographers term the “zone of accumulation”. They are compacted and under this pressure, the snow becomes ice, in this case a glacier called Öræfajökull Glacier. From this main glacier, tongues of ice extend out. These are tributary glaciers and one of them is called Fjallsjökull.

Where does Fjallsárlón get its water from?

Fjallsárlón sits in front of a glacier. This body of water began to form around 70 years ago, when Fjallsjökull glacier started to retreat in earnest. Earlier, when the ice had been pushing forwards, it had hollowed out the landscape, scraping out a basin that was in places about 100 metres below sea level.

When the glacier retreated, the meltwater continued to move forward under the influence of gravity and gradually filled up the space that had been created. Another glacier called Hrútárjökull also contributes some water. What you see is now the fourth deepest lake in the country.

However, this isn’t the only water that feeds the lagoon. Some is supplied courtesy of a river called Breiðá on the east side of the lagoon, which connects to another glacial lagoon named Breiðárlón. Like Jökulsárlón, it sits in front of Breiðamerkurjökull glacier. However, it’s different from both Fjallsárlón and Jökulsárlón as you won’t see any icebergs floating in it.

Fjallsárlón is located further inland than Jökulsárlón as seawater does not reach the lagoon it freezes during winter . Jökulsárlón’s case, the presence of this channel means that sea water can mix with glacial meltwater. Incidentally, when location scouts working on the Bond film Die Another Day chose the lagoon as the setting for a thrilling car chase, this channel had to be blocked off so the ice would be solid enough to take the weight – the salt content usually prevents the water from freezing (though it’s still pretty cold!).

What are some key features of glacial landscapes in and around Fjallsárlón?

As with all glacial landscapes, there’s plenty of evidence of sediment in the form of till and moraines. Till is the material that is eroded by the glacier and carried within, on top or underneath the ice. This is then deposited by a glacier as it moves; we call that moraine. So for instance, you’ll find what’s known as recessional moraines. When the glacier is in motion, it carries with it rocks and other material that it plucks off the valley floor.

However, when the glacier slows down or stops, it doesn’t have enough energy to carry this load any further and so it puts it down. As the glacier can advance or retreat, it’s common that such recessional moraines are covered over at some point by the ice and are concealed beneath the glacier. When a glacier shrinks, this might be uncovered again and become visible once more.

A glacier also has what’s known as a zone of ablation in its lower reaches. Another common feature of glacial scenery is an outwash plain, also known as sandar or sandur. This occurs when there is glacial outwash beyond the end of the glacier. Glacial meltwater contains some of the sediment that has previously been carried by the ice. The water effectively sorts what it is carrying, dropping the heaviest material first – closest to the end of the glacier – and washes smaller pieces further down.

In Iceland, we have a relatively large number of outwash plains. This is largely due to the presence of volcanoes beneath the ice caps and glaciers. When sub-glacial eruptions happen, the heat from the magma melts the ice and causes it to flow out of the glacier, sometimes suddenly and dramatically. These days, effective monitoring and warning systems mean people and livestock are evacuated, though this wasn’t always the case in the past.

Evidence of Fjallsjökull glacier retreat

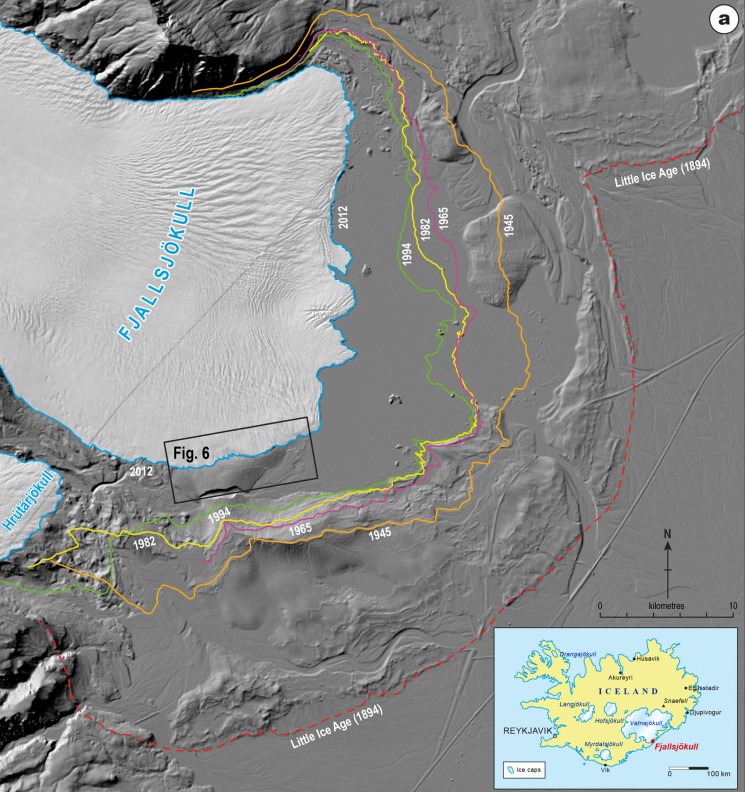

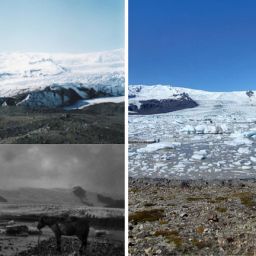

One of the hardest things to come to terms with when it comes to Iceland’s landscapes is that its glaciers are melting. Scientists mapping the extent of the Fjallsjökull glacier between 2012 and 2019 recorded what they term “substantial” glacier retreat where the ice meets land. However some parts of the glacier – representing about half of the ice – showed little change over the same period.

Some of the glacier, accounting for 94% of areas that showed measurable change, showed evidence of thinning, particularly right at the end, close to the glacier’s snout. There were a few areas higher up where the thickness of the ice had increased, but overall the volume of Fjallsjökull had shrunk during those seven years, retreating significantly as global temperatures rise.

It’s not a new phenomenon. In fact, it’s likely that the maximum extent of the glacier was recorded as far back as 1870, with the ice readvancing to the same extent a couple of decades later, in 1894. The Icelandic Glaciological Society has compiled measurements taken at intervals over time since the 1930s and the resultant map shows that the glacier has shrunk, though the rate of retreat has varied over time.

Nevertheless, if you take a boat tour out onto Fjallsárlón lagoon or come with us on a glacier hike, it’s hard to believe that this majestic body of ice could ever disappear. As you gaze up at the ice from your low vantage point on the Zodiac boat out on the water, you get a real sense of the enormous scale of this wonderful glacier. It’s a phenomenal sight and one you’ll treasure, no matter what the future brings.